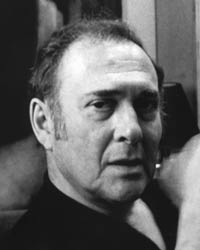

Harold Pinter was born in London in 1930. Noted as a master of contemporary theatre, his work bears comparison to the achievements of Samuel Beckett. Pinter started his career as an actor under the pseudonym David Baron, but after 1956 he began to write for the stage. His first full-length play, The Birthday Party, was produced in 1958, followed by The Caretaker (1960) which prompted international acclaim. Pinterís landscapes follow their own course, comprising over forty plays, twenty screenplays, poetry and prose. In 1995, he won the David Cohn British Literature Prize, awarded for a lifetimeís achievement in the theatre. Ashes to Ashes (1997) is in repertoire at the National Theatre in Prague. Various Voices, a collection of prose, poetry and politics spanning the past fifty years was recently published in London. Harold Pinter is married to Antonia Fraser.

Harold Pinter was born in London in 1930. Noted as a master of contemporary theatre, his work bears comparison to the achievements of Samuel Beckett. Pinter started his career as an actor under the pseudonym David Baron, but after 1956 he began to write for the stage. His first full-length play, The Birthday Party, was produced in 1958, followed by The Caretaker (1960) which prompted international acclaim. Pinterís landscapes follow their own course, comprising over forty plays, twenty screenplays, poetry and prose. In 1995, he won the David Cohn British Literature Prize, awarded for a lifetimeís achievement in the theatre. Ashes to Ashes (1997) is in repertoire at the National Theatre in Prague. Various Voices, a collection of prose, poetry and politics spanning the past fifty years was recently published in London. Harold Pinter is married to Antonia Fraser.

Old Times

Act two

DEELEY: Like the room?

ANNA: Yes.

D: We sleep here. These are beds. The great thing about these beds is that they are susceptible to any amount of permutation. They can be separated as they are now. Or placed at right angles, or one can bisect the other, or you can sleep feet to feet, or head to head, or side by side. Itís the castors that make all this possible.

He sits with coffee.

Yes, I remember you quite clearly from The Wayfarers.

A: The what?

D: The Wayfarers Tavern, just off the Brompton Road.

A: When was that?

D: Years ago.

A: I donít think so.

D: Oh yes, it was you, no question. I never forget a face. You sat in the corner, quite often, sometimes alone, sometimes with others. And here you are, sitting in my house in the country. The same woman. Incredible. Fellow called Luke used to go in there. You knew him.

A: Luke?

D: Big chap. Ginger hair. Ginger beard.

A: I donít honestly think so.

D: Yes, a whole crowd of them, poets, stunt men, jockeys, stand-up comedians, that kind of setup. You used to wear a scarf, thatís right, a black scarf, and a black sweater, and a skirt.

A: Me?

D: And black stockings. Donít tell me youíve forgotten. The Wayfarers Tavern? You might have forgotten the name but you must remember the pub. You were the darling of the saloon bar.

A: I wasnít rich, you know. I didnít have money for alcohol.

D: You had escorts. You didnít have to pay. You were looked after. I bought you a few drinks myself.

A: You?

D: Sure.

A: Never.

D: Itís the truth. I remember clearly.

Pause

A: You?

D: Iíve bought you drinks.

Pause

Twenty years agoÖ or so.

A: Youíre saying weíve met before?

D: Of course weíve met before.

Pause

Weíve talked before. In that pub, for example. In the corner. Luke didnít like it much but we ignored him. Later we all went to a party. Someoneís flat, somewhere in Westbourne Grove. You sat on a very low sofa, I sat opposite and looked up your skirt. Your black stockings were very black because your thighs were so white. Thatís something thatís all over now, of course, isnít it, nothing like the same palpable profit in it now, itís all over. But it was worthwhile then. It was worthwhile that night. I simply sat sipping my light ale and gazedÖ gazed up your skirt. You didnít object, you found my gaze perfectly acceptable.

A: I was aware of your gaze, was I?

D: There was a great argument going on, about China or something, or death, or China and death, I canít remember which, but nobody but I had a thigh-kissing view, nobody but you had the thighs which kissed. And here you are. Same woman. Same thighs.

Pause

Yes. Then a friend of yours came in, a girl, a girl friend. She sat on the sofa with you, you both chatted and chuckled, sitting together, and I settled lower to gaze at you both, at both your thighs, squealing and hissing, you aware, she unaware, but then a great multitude of men surrounded me and demanded my opinion about death, or about China, or whatever it was, and they would not let me be but bent down over me, so that what with their stinking breath and their broken teeth and the hair in their noses and China and death and their arses on the arms of my chair I was forced to get up and plunge my way through them, followed by them, followed by them with ferocity, as if I were the cause of their argument, looking back through smoke, rushing to the table with the linoleum cover to look for one more full bottle of light ale, looking back through smoke, glimpsing two girls on the sofa, one of them you, heads close, whispering, no longer able to see anything, no longer able to see stocking or thigh, and then you were gone. I wandered over to the sofa. There was no one on it. I gazed at the indentations of four buttocks. Two of which were yours.

Pause

A: Iíve rarely heard a sadder story.

D: I agree.

A: Iím terribly sorry.

D: Thatís all right.

Pause.

I never saw you again. You disappeared from the area. Perhaps you moved out.

A: No. I didnít.

D: I never saw you in The Wayfarers Tavern again. Where were you?

A: Oh, at concerts, I should think, or the ballet.

Silence

Kateyís taking a long time over her bath.

D: Well, you know what sheís like when she gets in the bath.

A: Yes.

D: Enjoys it Takes a long time over it.

A: She does, yes.

D: A hell of a long time. Luxuriates in it. Gives herself a great soaping all over.

Pause

Really soaps herself all over, and then washes the soap off, sud by sud. Meticulously. Sheís both thorough and, I must say it, sensuos. Gives herself a comprehensive going over, and apart from everything else she does emerge as clean as a new pin. Donít you think?

A: Very clean.

D: Truly so. Not a speck. Not a tidemark. Shiny as a balloon.

A: Yes, a kind of floating.

D: What?

A: She floats from the bath. Like a dream. Unaware of anyone standing, with her towel, waiting for her, waiting to wrap it round her. Quite absorbed.

Pause

Until the towel is placed on her shoulders.

Pause

D: Of course sheís so totally incompetent at drying herself properly, did you find that? She gives herself a really good scrub, but can she with the same efficiency give herself an equally good rub? I have found, in my experience of her, that this is not in fact the case. Youíll always find a few odd unexpected unwanted cheeky globules dripping about.

A: Why donít you dry her yourself?

D: Would you recommend that?

A: Youíd do it properly.

D: In her bath towel?

A: How out?

D: How out?

A: How could you dry her out? Out of her bath towel?

D: I donít know.

A: Well, dry her yourself, in her bath towel.

Pause

D: Why donít you dry her in her bath towel?

A: Me?

D: Youíd do it properly.

A: No, no.

D: Surely? I mean, youíre a woman, you know how and where and in what density moisture collects on womenís bodies.

A: No two women are the same.

D: Well, thatís true enough.

Pause

Iíve got a brilliant idea. why donít we do it with powder?

A: Is that a brilliant idea?

D: Isnít it?

A: Itís quite common to powder yourself after a bath.

D: Itís quite common to powder yourself after a bath but itís quite uncommon to be powdered. Or is it? Itís not common where I come from, I can tell you. My mother would have a fit.

Pause

Listen. Iíll tell you what. Iíll do it. Iíll do the whole lot. The towel and the powder. After all, I am her husband. But you can supervise the whole thing. And give me some hot tips while youíre at it. Thatíll kill two birds with one stone.

Pause

(To himself.) Christ.

He looks at her slowly.

You must be about forty, I should think, by now.

Pause

If I walked into The Wayfarers Tavern now, and saw you sitting in the corner, I wouldnít recognize you.

The Birthday Party

GOLDBERG: Lift your glasses, ladies and gentlemen. Weíll drink a toast.

MEG: Lulu isnít here.

GOLDBERG: Itís past the hour. Now Ė whoís going to propose the toast? Mrs. Boles, it can only be

you.

MEG: Me?

GOLDBERG: Who else?

MEG: But what do I say?

GOLDBERG: Say what you feel. What you honesty feel. (MEG looks uncertain) Itís Stanleyís birthday

Your Stanley. Look at him. Look at him and itíll come. Wait a minute, the lightís too strong. Letís

have proper lighting. McCann, have you got your torch?

MCCANN: (bringing a small torch from his pocket) Here.

GOLDBERG: Switch out the light and put on your torch. (MCCANN goes to the door, switches off the

light, comes back, shines the torch on MEG. Outside the window there is still a faint light.) Not on

the lady, on the gentleman! You must shine it on the birthday boy. (MCCANN shines the torch in

STANLEYís face.) Now, Mrs. Boles, itís all yours.

Pause.

MEG: I donít know what to say.

GOLDBERG: Look at him. Just look at him.

MEG: Isnít the light in his eyes?

GOLDBERG: No, no. Go on.

MEG: Well Ė itís very nice to be here tonight, in my house, and I want to propose a toast to Stanley, because itís his birthday, and heís lived here for a long while now, and heís my Stanley now. And I think heís a good boy, although sometimes heís bad. (An appreciative laugh from GOLDBERG.) And heís the only Stanley I know, and I know him better than all the world, although he doesnít think so. (ďHear Ė hearĒ from GOLDBERG.) Well, I could cry because Iím so happy, having him here and not gone away, on his birthday, and there isnít anything I wouldnít do for him, and all you good people here tonight Ö (She sobs.)

GOLDBERG: Beautiful! A beautiful speech. Put the light on, McCann. (MCCAN goes to the door. STANLEY remains still.) That was a lovely toast. (The lights goes on. LULU enters from the door, left. GOLDBERG comforts MEG.) Buck up now. Come on, smile at the birdy. Thatís better. Ah, whoís here.

MEG: Lulu.

GOLDBERG: How do you do, Lulu? Iím Nat Goldberg.

LULU: Hallo.

GOLDBERG: Stanley, a drink for your guest. Stanley. (STANLEY hands a glass to LULU.) Right. Now raise your glasses. Everyone standing up? No, not you, Stanley. You must sit down.

MCCANN: Yes, thatís right. He must sit down.

GOLDBERG: You donít mind sitting down a minute? Weíre going to drink to you.

MEG: Come on!

LULU: Come on!

STANLEY sits in a chair at the table.

GOLDBERG: Right. Now Stanleyís sat down. (Taking the stage.) Well, I want to say first that Iíve never been so touched to the heart as by the toast weíve just heard. How often, in this day and age, do you come across real, true warmth? Once in a lifetime. Until a few minutes ago, ladies and gentlemen, I, like all of you, was asking the same question. Whatís happened to the love, the bonhomie, the unashamed expression of affection of the day before yesterday, that our mums taught us in the nursery?

MCCANN: Gone with the wind.

GOLDBERG: Thatís what I thought, until today. I believe in a good laugh, a dayís fishing, a bit of gardening. I was very proud of my old greenhouse, made out of my own spit and faith. Thatís the sort of man I am. Not size but quality. A little Austin, tea in Fullers, a library book from Boots, and Iím satisfied. But just now, I say just now, the lady of the house said her piece and I for one am knocked over by the sentiments she expressed. Lucky is the man whoís at the receiving end, thatís what I say. (Pause.) How can I put it to you? We all wander on our tod through this world. Itís a lonely pillow to kip on. Right!

LULU: (admiringly) Right!

GOLDBERG: Agreed. But tonight, Lulu, McCann, weíve known a great fortune. Weíve heard a lady extend the sum total of her devotion, in all its pride, plume and peacock, to a member of her own living race. Stanley, my heartfelt congratulations. I wish you, on behalf of us all, a happy birthday. Iím sure youíve been a prouder man than you are today. Mazoltov! And may we only meet at Simchahs! (LULU and MEG applaud.) Turn out the light, McCann, while we drink the toast.

LULU: That was a wonderful speech.

MCCANN switches out the light, comes back, and shines the torch in STANLEYís face. The light outside the window is fainter.

GOLDBERG: Lift your glasses. Stanley Ė happy birthday.

MCCANN: Happy birthday.

LULU: Happy birthday.

MEG: Many happy returns of the day, Stan.

GOLDBERG: And well over the fast.

Act two

DEELEY: Like the room?

ANNA: Yes.

D: We sleep here. These are beds. The great thing about these beds is that they are susceptible to any amount of permutation. They can be separated as they are now. Or placed at right angles, or one can bisect the other, or you can sleep feet to feet, or head to head, or side by side. Itís the castors that make all this possible.

He sits with coffee.

Yes, I remember you quite clearly from The Wayfarers.

A: The what?

D: The Wayfarers Tavern, just off the Brompton Road.

A: When was that?

D: Years ago.

A: I donít think so.

D: Oh yes, it was you, no question. I never forget a face. You sat in the corner, quite often, sometimes alone, sometimes with others. And here you are, sitting in my house in the country. The same woman. Incredible. Fellow called Luke used to go in there. You knew him.

A: Luke?

D: Big chap. Ginger hair. Ginger beard.

A: I donít honestly think so.

D: Yes, a whole crowd of them, poets, stunt men, jockeys, stand-up comedians, that kind of setup. You used to wear a scarf, thatís right, a black scarf, and a black sweater, and a skirt.

A: Me?

D: And black stockings. Donít tell me youíve forgotten. The Wayfarers Tavern? You might have forgotten the name but you must remember the pub. You were the darling of the saloon bar.

A: I wasnít rich, you know. I didnít have money for alcohol.

D: You had escorts. You didnít have to pay. You were looked after. I bought you a few drinks myself.

A: You?

D: Sure.

A: Never.

D: Itís the truth. I remember clearly.

Pause

A: You?

D: Iíve bought you drinks.

Pause

Twenty years agoÖ or so.

A: Youíre saying weíve met before?

D: Of course weíve met before.

Pause

Weíve talked before. In that pub, for example. In the corner. Luke didnít like it much but we ignored him. Later we all went to a party. Someoneís flat, somewhere in Westbourne Grove. You sat on a very low sofa, I sat opposite and looked up your skirt. Your black stockings were very black because your thighs were so white. Thatís something thatís all over now, of course, isnít it, nothing like the same palpable profit in it now, itís all over. But it was worthwhile then. It was worthwhile that night. I simply sat sipping my light ale and gazedÖ gazed up your skirt. You didnít object, you found my gaze perfectly acceptable.

A: I was aware of your gaze, was I?

D: There was a great argument going on, about China or something, or death, or China and death, I canít remember which, but nobody but I had a thigh-kissing view, nobody but you had the thighs which kissed. And here you are. Same woman. Same thighs.

Pause

Yes. Then a friend of yours came in, a girl, a girl friend. She sat on the sofa with you, you both chatted and chuckled, sitting together, and I settled lower to gaze at you both, at both your thighs, squealing and hissing, you aware, she unaware, but then a great multitude of men surrounded me and demanded my opinion about death, or about China, or whatever it was, and they would not let me be but bent down over me, so that what with their stinking breath and their broken teeth and the hair in their noses and China and death and their arses on the arms of my chair I was forced to get up and plunge my way through them, followed by them, followed by them with ferocity, as if I were the cause of their argument, looking back through smoke, rushing to the table with the linoleum cover to look for one more full bottle of light ale, looking back through smoke, glimpsing two girls on the sofa, one of them you, heads close, whispering, no longer able to see anything, no longer able to see stocking or thigh, and then you were gone. I wandered over to the sofa. There was no one on it. I gazed at the indentations of four buttocks. Two of which were yours.

Pause

A: Iíve rarely heard a sadder story.

D: I agree.

A: Iím terribly sorry.

D: Thatís all right.

Pause.

I never saw you again. You disappeared from the area. Perhaps you moved out.

A: No. I didnít.

D: I never saw you in The Wayfarers Tavern again. Where were you?

A: Oh, at concerts, I should think, or the ballet.

Silence

Kateyís taking a long time over her bath.

D: Well, you know what sheís like when she gets in the bath.

A: Yes.

D: Enjoys it Takes a long time over it.

A: She does, yes.

D: A hell of a long time. Luxuriates in it. Gives herself a great soaping all over.

Pause

Really soaps herself all over, and then washes the soap off, sud by sud. Meticulously. Sheís both thorough and, I must say it, sensuos. Gives herself a comprehensive going over, and apart from everything else she does emerge as clean as a new pin. Donít you think?

A: Very clean.

D: Truly so. Not a speck. Not a tidemark. Shiny as a balloon.

A: Yes, a kind of floating.

D: What?

A: She floats from the bath. Like a dream. Unaware of anyone standing, with her towel, waiting for her, waiting to wrap it round her. Quite absorbed.

Pause

Until the towel is placed on her shoulders.

Pause

D: Of course sheís so totally incompetent at drying herself properly, did you find that? She gives herself a really good scrub, but can she with the same efficiency give herself an equally good rub? I have found, in my experience of her, that this is not in fact the case. Youíll always find a few odd unexpected unwanted cheeky globules dripping about.

A: Why donít you dry her yourself?

D: Would you recommend that?

A: Youíd do it properly.

D: In her bath towel?

A: How out?

D: How out?

A: How could you dry her out? Out of her bath towel?

D: I donít know.

A: Well, dry her yourself, in her bath towel.

Pause

D: Why donít you dry her in her bath towel?

A: Me?

D: Youíd do it properly.

A: No, no.

D: Surely? I mean, youíre a woman, you know how and where and in what density moisture collects on womenís bodies.

A: No two women are the same.

D: Well, thatís true enough.

Pause

Iíve got a brilliant idea. why donít we do it with powder?

A: Is that a brilliant idea?

D: Isnít it?

A: Itís quite common to powder yourself after a bath.

D: Itís quite common to powder yourself after a bath but itís quite uncommon to be powdered. Or is it? Itís not common where I come from, I can tell you. My mother would have a fit.

Pause

Listen. Iíll tell you what. Iíll do it. Iíll do the whole lot. The towel and the powder. After all, I am her husband. But you can supervise the whole thing. And give me some hot tips while youíre at it. Thatíll kill two birds with one stone.

Pause

(To himself.) Christ.

He looks at her slowly.

You must be about forty, I should think, by now.

Pause

If I walked into The Wayfarers Tavern now, and saw you sitting in the corner, I wouldnít recognize you.

The Birthday Party

GOLDBERG: Lift your glasses, ladies and gentlemen. Weíll drink a toast.

MEG: Lulu isnít here.

GOLDBERG: Itís past the hour. Now Ė whoís going to propose the toast? Mrs. Boles, it can only be

you.

MEG: Me?

GOLDBERG: Who else?

MEG: But what do I say?

GOLDBERG: Say what you feel. What you honesty feel. (MEG looks uncertain) Itís Stanleyís birthday

Your Stanley. Look at him. Look at him and itíll come. Wait a minute, the lightís too strong. Letís

have proper lighting. McCann, have you got your torch?

MCCANN: (bringing a small torch from his pocket) Here.

GOLDBERG: Switch out the light and put on your torch. (MCCANN goes to the door, switches off the

light, comes back, shines the torch on MEG. Outside the window there is still a faint light.) Not on

the lady, on the gentleman! You must shine it on the birthday boy. (MCCANN shines the torch in

STANLEYís face.) Now, Mrs. Boles, itís all yours.

Pause.

MEG: I donít know what to say.

GOLDBERG: Look at him. Just look at him.

MEG: Isnít the light in his eyes?

GOLDBERG: No, no. Go on.

MEG: Well Ė itís very nice to be here tonight, in my house, and I want to propose a toast to Stanley, because itís his birthday, and heís lived here for a long while now, and heís my Stanley now. And I think heís a good boy, although sometimes heís bad. (An appreciative laugh from GOLDBERG.) And heís the only Stanley I know, and I know him better than all the world, although he doesnít think so. (ďHear Ė hearĒ from GOLDBERG.) Well, I could cry because Iím so happy, having him here and not gone away, on his birthday, and there isnít anything I wouldnít do for him, and all you good people here tonight Ö (She sobs.)

GOLDBERG: Beautiful! A beautiful speech. Put the light on, McCann. (MCCAN goes to the door. STANLEY remains still.) That was a lovely toast. (The lights goes on. LULU enters from the door, left. GOLDBERG comforts MEG.) Buck up now. Come on, smile at the birdy. Thatís better. Ah, whoís here.

MEG: Lulu.

GOLDBERG: How do you do, Lulu? Iím Nat Goldberg.

LULU: Hallo.

GOLDBERG: Stanley, a drink for your guest. Stanley. (STANLEY hands a glass to LULU.) Right. Now raise your glasses. Everyone standing up? No, not you, Stanley. You must sit down.

MCCANN: Yes, thatís right. He must sit down.

GOLDBERG: You donít mind sitting down a minute? Weíre going to drink to you.

MEG: Come on!

LULU: Come on!

STANLEY sits in a chair at the table.

GOLDBERG: Right. Now Stanleyís sat down. (Taking the stage.) Well, I want to say first that Iíve never been so touched to the heart as by the toast weíve just heard. How often, in this day and age, do you come across real, true warmth? Once in a lifetime. Until a few minutes ago, ladies and gentlemen, I, like all of you, was asking the same question. Whatís happened to the love, the bonhomie, the unashamed expression of affection of the day before yesterday, that our mums taught us in the nursery?

MCCANN: Gone with the wind.

GOLDBERG: Thatís what I thought, until today. I believe in a good laugh, a dayís fishing, a bit of gardening. I was very proud of my old greenhouse, made out of my own spit and faith. Thatís the sort of man I am. Not size but quality. A little Austin, tea in Fullers, a library book from Boots, and Iím satisfied. But just now, I say just now, the lady of the house said her piece and I for one am knocked over by the sentiments she expressed. Lucky is the man whoís at the receiving end, thatís what I say. (Pause.) How can I put it to you? We all wander on our tod through this world. Itís a lonely pillow to kip on. Right!

LULU: (admiringly) Right!

GOLDBERG: Agreed. But tonight, Lulu, McCann, weíve known a great fortune. Weíve heard a lady extend the sum total of her devotion, in all its pride, plume and peacock, to a member of her own living race. Stanley, my heartfelt congratulations. I wish you, on behalf of us all, a happy birthday. Iím sure youíve been a prouder man than you are today. Mazoltov! And may we only meet at Simchahs! (LULU and MEG applaud.) Turn out the light, McCann, while we drink the toast.

LULU: That was a wonderful speech.

MCCANN switches out the light, comes back, and shines the torch in STANLEYís face. The light outside the window is fainter.

GOLDBERG: Lift your glasses. Stanley Ė happy birthday.

MCCANN: Happy birthday.

LULU: Happy birthday.

MEG: Many happy returns of the day, Stan.

GOLDBERG: And well over the fast.